Table of Contents

Introduction

A remedy proving is an essential component of classical homeopathy. Through remedy proving, it is determined as objectively as possible which symptoms belong to a specific remedy. Samuel Hahnemann discovered remedy proving because he was quite critical of what people wrote and wanted to test for himself what various people claimed.

A remedy proving is an essential component of classical homeopathy. Through remedy proving, it is determined as objectively as possible which symptoms belong to a specific remedy. Samuel Hahnemann discovered remedy proving because he was quite critical of what people wrote and wanted to test for himself what various people claimed.

Broadly speaking, the proving consists of selecting participants, a baseline measurement, the actual proving with increasingly potentized remedies, and analyzing the data. Besides remedy proving, poisonings also provide information about the symptoms associated with a particular remedy. In brief: a remedy proving is a voluntary test of a non-toxic dose of a substance. Poisoning is an unintentional voluntary test of a toxic dose of a substance.

There are also methods sometimes used that are unsuitable because they provide unreliable information. The information known about homeopathic (potentized) remedies is described in a so-called materia medica.

Importance of the proving

A remedy proving, or sometimes called drug proving, is an essential part of classical homeopathy. This concept is such a crucial pillar of classical homeopathy that homeopathy cannot exist without it. A proving is a way to objectively discover which symptoms can be treated with a homeopathic remedy. It is clear that without remedy proving, it would ultimately be impossible to prescribe remedies to patients.

Origin of remedy proving

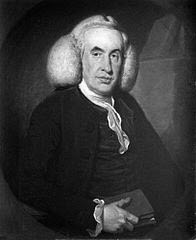

To explain what remedy proving is, we must first dive into history, as the context of the origin of remedy proving is essential to understanding it. After Hahnemann became dissatisfied and stopped practicing regular medicine (around 1785), he began translating books (chapter 5, Samuel Hahnemann: His Life and Works). This was a logical choice because he had an exceptional talent for languages. Probably due to his critical nature, Hahnemann did not translate books as we would expect a translator to do today. In his translations, he included critical comments about the content and sometimes even corrected the original text.

At some point (1790), he translated a materia medica written by William Cullen and reached a point where Cullen described that the bark of the cinchona tree was good for fighting malaria due to its bitter taste and its effect on the stomach.  Hahnemann wondered about the validity of this claim. He questioned whether it was true that cinchona bark had this specific effect on the stomach. To test this, he decided to ingest certain amounts of the bark to see if it really had this effect. During this test, he noticed that he developed malaria-like symptoms while he could not have malaria. This led him to question whether the effect of cinchona bark was due to its tonic effect on the stomach or a relationship with the effect of the substance on relatively healthy people. This is well-documented in Richard Haehl’s book “Samuel Hahnemann: His Life and Work,” volume 1, pages 36 to 40.

Hahnemann wondered about the validity of this claim. He questioned whether it was true that cinchona bark had this specific effect on the stomach. To test this, he decided to ingest certain amounts of the bark to see if it really had this effect. During this test, he noticed that he developed malaria-like symptoms while he could not have malaria. This led him to question whether the effect of cinchona bark was due to its tonic effect on the stomach or a relationship with the effect of the substance on relatively healthy people. This is well-documented in Richard Haehl’s book “Samuel Hahnemann: His Life and Work,” volume 1, pages 36 to 40.

Hahnemann further investigated this hypothesis by testing other remedies in the same way and carefully documenting which symptoms developed after taking the remedy. Thus, he arrived at a solid method to determine for which combination of symptoms a remedy can be prescribed. It is important to realize that regular medicine at that time consisted of prescribing remedies based on symbolism, custom, assumptions, superstition, etc. There was no reliable scientific method to determine the effects of certain medicines. This was a thorn in Hahnemann’s side, and thus a scientific and substantiated method of determining the therapeutic effects of remedies appealed to him.

The concept of ‘Prüfung’ (proving)

Due to his critical and investigative attitude, Hahnemann came up with the idea that it is possible to test the effect of homeopathic remedies in an objective and reliable way, free from speculations. Because the therapeutic value of a remedy was determined by a method that tested each remedy, Hahnemann called this a ‘Prüfung.’ This term has been translated into English as ‘Proving.’ The meaning of the word ‘Prüfung’ illustrates the independent and scientific character of this remedy proving.

Conditions for a remedy proving

After discovering the concept of remedy proving, Hahnemann further refined and described rules for it. After years of experimenting and testing, he described the basic ideas for a classical homeopathic remedy proving in the article ‘Essay on a New Principle for Ascertaining the Curative Powers of Drugs‘ (1796). In the Organon, Hahnemann describes the basic rules for remedy proving in paragraphs 105-114 and 121-142. All the rules for remedy proving boil down to several basic concepts, which we will discuss below.

Pure

A remedy proving must be pure in several ways. Firstly, the raw material being tested must be as pure as possible. There should be no contamination of the raw material, as this could influence the results of the proving.

Additionally, there should be no external influences on the participants in a proving, such as changes in diet, starting or stopping medication, negative or positive emotional experiences, etc. The aim is for participants’ lives to remain as constant as possible during a remedy proving.

To get a pure picture of which symptoms belong to a remedy, it is useful for a participant not to have various health complaints during a remedy proving. It is not easy to find perfectly healthy individuals for a remedy proving. However, it is not necessary to be perfectly healthy because there is a solution for this. By having participants keep a diary in the weeks before the remedy proving starts, it can be documented which complaints someone already had. This can be taken into account during the analysis of the data after the remedy proving.

Objective

Hahnemann used remedy proving to determine which symptoms can be healed with a specific remedy in an objective and logical way. He wanted to move away from prescribing based on speculation, symbolism, assumptions, dogma, and wrong assumptions. Therefore, participants must precisely record any changes in their health during a remedy proving.

Hahnemann used remedy proving to determine which symptoms can be healed with a specific remedy in an objective and logical way. He wanted to move away from prescribing based on speculation, symbolism, assumptions, dogma, and wrong assumptions. Therefore, participants must precisely record any changes in their health during a remedy proving.

To prevent bias, participants should not know which substance the remedy is made from. This prevents this knowledge from influencing their experiences. Participants should also not communicate with each other about the proving.

Ideally, some participants receive a placebo instead of the remedy to more confidently attribute observed phenomena to the remedy being tested.

Consistent / reproducibility

A remedy proving must be conducted so that the information is reproducible. Of course, each participant has different sensitivities and weak spots, meaning the proving can never be repeated exactly the same way. However, the remedy proving process should be broadly reproducible, allowing knowledge about a remedy to be continuously expanded.

The course of a remedy proving

A remedy proving generally proceeds as follows:

1. Selection of participants: Participants must meet specific criteria. They should be able to communicate well, have a relatively stable life situation, and be relatively healthy.

2. Baseline measurement: Participants keep a diary for a period before the actual proving, recording their symptoms. This information helps separate the symptoms caused by the remedy from those pre-existing in the participant.

3. Proving with increasing potencies from low to high: During the actual proving, participants take the remedy at a fixed frequency. When they notice changes, they stop taking the remedy. During this phase, they keep a detailed diary of all changes. Participants do not know which remedy they are taking, do not communicate with each other about the proving, and preferably, there is also a placebo group.

4. Data analysis: After the proving, the data recorded in the diaries are analyzed. Symptoms present before the proving began are eliminated for each participant. The rest is collectively analyzed to identify patterns, such as symptoms occurring in multiple participants. There is also an examination of symptoms attributable to the placebo effect by comparing the placebo group with the actual remedy group.

What is not a remedy proving?

Having described what a remedy proving is, it is easy to describe what it is not. It is essential to consider this because other methods are increasingly used to add information to the materia medica today. These methods result in incorrect or speculative information, mixing with reliable information and making it harder to find the correct remedy for the right patient.

To meet the criteria of a classical homeopathic remedy proving, each method must follow the described basic rules. Below we explain some methods gaining popularity today but do not align with the basic principles.

Family analysis / Doctrine of signatures / Systems thinking

A popular method is using the periodic table or classifying groups of remedies according to patterns. Symbolic characteristics of the group to which a remedy belongs are used to assign symptoms to a particular remedy. Examples include remedies made from iron, characterized by hardness and combativeness, because iron is hard and used to make weapons. Another example is remedies made from plants associated with flexibility, colorfulness, etc. It is a form of systems thinking where the doctrine of signatures plays a crucial role.

However, these methods do not involve a remedy proving. Using symbolism is a speculative and unreliable way to determine the effects of potentized remedies. The founder of homeopathy, Hahnemann, designed the remedy proving specifically to avoid symbolism, speculation, and assumptions. In the article ‘Essay on a New Principle for Ascertaining the Curative Powers of Drugs,’ he writes: ‘I do not in any way deny the many important indications that the natural system can offer to the philosophical student of the materia medica and to the one who considers it his duty to discover new medicinal substances; but these indications can only help to confirm known facts and serve as commentary, or in the case of untested plants, they can give rise to hypothetical assumptions that are far from likely.’

Meditation or Dream Proving

Another method we frequently encounter is a proving based on meditation or dreams. Here, a substance is meditated upon, or the remedy is placed under the pillow during sleep. The images that arise during meditation or dreams are used to describe the remedy. Of course, this method has many drawbacks. For example, how do you distinguish images caused by the remedy from those arising from expectations, fears, and other factors? We also do not know with certainty whether physical contact is necessary for the effect of a potentized remedy. For this reason, a proving without physical contact is dubious. Additionally, a regular remedy proving usually lasts longer (sometimes several weeks), whereas it is not possible to meditate or dream for weeks.

Another method we frequently encounter is a proving based on meditation or dreams. Here, a substance is meditated upon, or the remedy is placed under the pillow during sleep. The images that arise during meditation or dreams are used to describe the remedy. Of course, this method has many drawbacks. For example, how do you distinguish images caused by the remedy from those arising from expectations, fears, and other factors? We also do not know with certainty whether physical contact is necessary for the effect of a potentized remedy. For this reason, a proving without physical contact is dubious. Additionally, a regular remedy proving usually lasts longer (sometimes several weeks), whereas it is not possible to meditate or dream for weeks.

Group proving

In a group proving, remedies are distributed during a seminar or other gathering for participants to take. At the end of the meeting (often 1-2 days later), findings are discussed in the group. However, participants have contact with each other and can influence each other. There is no baseline measurement, and there are too many external influences affecting the proving.

Trituration proving

In a trituration proving, a group of people triturate a remedy, meaning they grind the substance with lactose in a mortar. During this process, emotions and other changes are recorded and discussed. It is evident that such a test is not objective due to too much mutual influence and the test’s short duration.

Conclusion

The common denominator of all these modern methods is that the reliability of information obtained about remedies is much lower than that from an original remedy proving, clinical confirmation, and poisoning. There is too much uncertainty, and too much reliance on assumptions, interpretations, and symbolism. Another significant problem is that this information often does not match what we have found through more reliable methods. This contradiction raises questions about these methodologies.

These methods contradict the reason the founder designed the original remedy proving: to eliminate speculation, fantasy, and assumptions from medicine. These developments do not benefit the reputation of homeopathy because they represent a regression to the period before Hahnemann when speculation and fantasy formed the basis of therapies.

Poisoning

In extension of a remedy proving, poisoning also provides information. It may sound strange, but information obtained from poisoning can be used to determine what a homeopathic remedy can be used for. Poisoning provides information about toxic influences on the human body. It is clear that this is not organized and is always based on accidents. To use poisoning as a reliable source of information, certain conditions must be met.

In extension of a remedy proving, poisoning also provides information. It may sound strange, but information obtained from poisoning can be used to determine what a homeopathic remedy can be used for. Poisoning provides information about toxic influences on the human body. It is clear that this is not organized and is always based on accidents. To use poisoning as a reliable source of information, certain conditions must be met.

Firstly, it must be clear what caused the poisoning. If it is not 100% clear, the information is unusable. Secondly, the symptoms must be described as clearly as possible. A vague or general description does not provide usable information.

In the homeopathic materia medica, many symptoms are described by people who, for example, worked in a factory where they came into contact with certain substances. Some of the symptoms described for the remedy Mercurius Solubilis come from descriptions of the so-called mad hatter’s disease. Another example is descriptions of medication side effects people experienced. For instance, in the mid-19th century, potassium bromide was prescribed for convulsive diseases such as epilepsy. Known side effects included sedation, depression, and acne.

Although this is very unpleasant for the affected individuals, this information is usable for supplementing the materia medica. Thus, something bad is converted into something good.

In summary: poisoning is an unintentional test of a toxic dose of a substance, while a remedy proving is a voluntary test of a non-toxic dose of a substance.

Remedy proving and training to become a classical homeopath

It is, of course, necessary to know how a remedy proving works and its purpose. This belongs to the background knowledge every homeopath must have. A major reason to know the backgrounds of remedy proving is to determine why certain other methods are not usable and what the consequences are. In our training, you learn all about remedy proving early in the first year. We have created a special e-learning module for this, and we discuss it during classroom lessons.

It is not necessary or desirable to conduct a remedy proving during the training, as a good proving is too extensive to do with a small group. Besides, taking a remedy during a remedy proving temporarily affects health. For this reason, we do not require a remedy proving from our students.

Sources

- Hahnemann, S. (1991). Organon of Medicine (6th ed., W. Boericke, Trans.). New Delhi: B. Jain Publishers. (Original work published in 1842). ISBN 8170210852

- Hahnemann, S. (1987). The Lesser Writings of Samuel Hahnemann. New Delhi: B. Jain Publishers.

- Haehl, R. (2002). Samuel Hahnemann: His Life and Work. New Delhi: B. Jain Publishers. ISBN 8170216923

- Kent, J. T. (2003). Lectures on Homoeopathic Philosophy. London: Homoeopathic Publishing Company. ISBN 1869975057

- Vithoulkas, G. (1980). The Science of Homeopathy. New York, NY: Grove Press. ISBN 0802151205