Introduction and summary

In classical homeopathy, the concept of the “similimum” is essential. It refers to the unique remedy that aligns closely with the patient’s entire disease profile. This article discusses the importance of this concept and explains why, in classical homeopathy, a single remedy is prescribed at a time, with careful interim evaluations. Through an example, the principle of the similimum will be clarified. Additionally, the various approaches within (classical) homeopathy are discussed, enabling both prospective students and those considering homeopathic treatment to make choices that align with their expectations.

Table of Contents

Meaning of the word Similimum

The word ‘similimum’ is derived from the Latin ‘simillimus,’ meaning ‘the most similar.’ This originates from ‘simili,’ meaning ‘similar’ or ‘comparable’—a relation seen in the English word “similar.” Using this term emphasizes the idea of a remedy that closely matches the patient’s complete disease picture. This term was first introduced by Samuel Hahnemann in classical homeopathy. Hahnemann describes that not just one part of a person—such as a thumb, knee, psyche, or lungs—is diseased, but that the person as a whole is unwell. Symptoms only manifest in areas that are weak points for the specific patient.

For a classical homeopath, this means that a remedy must match the patient’s entire disease profile. More about this concept can be found in the article What is the Concept of ‘Totality’ According to Classical Homeopathy?

This is also why, during the intake, a homeopath does not only look at the main complaint but also considers other symptoms, general conditions, psychological symptoms, and other issues the patient may be experiencing. The aim is not to treat based on a diagnosis but to find a single remedy that fits the patient as a whole.

Why is the similimum a core concept in classical homeopathy?

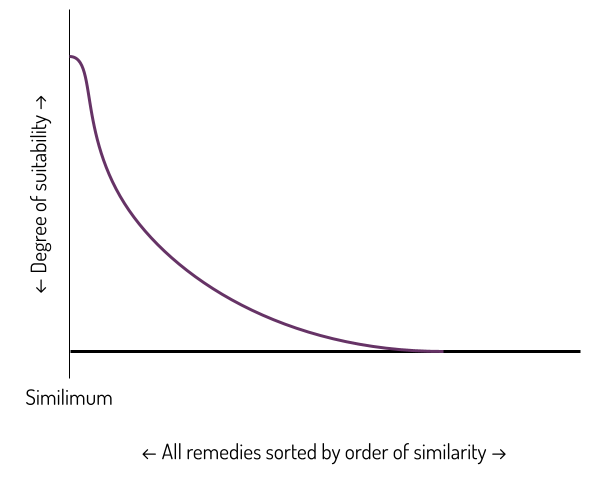

The concept of the ‘similimum’ sets classical homeopathy apart from other approaches within complementary and conventional medicine. The idea that there is one specific remedy that covers the patient’s entire disease picture is unique to classical homeopathy.

Example of applying the similimum principle

Example of applying the similimum principle

An example can help clarify the concept of the similimum. Imagine a patient present with the following complaints:

- There is an intense fear of infections. This fear has been present for several years and limits the patient’s daily life to some extent.

- The patient sleeps poorly and wakes up early in the morning with a strong urge to defecate, often experiencing diarrhea. According to the partner, the stool has a strongly unpleasant odor.

- The patient frequently suffers from headaches but finds it difficult to describe the nature of the pain or identify factors that influence it.

- There is a strong craving for spicy or seasoned food, coupled with a clear aversion to bitter flavors and organ meats.

- The patient experiences dizziness, particularly when in a warm room.

- Lastly, there is eczema in the elbow folds, with itchy, red, and dry patches.

A classical homeopath would aim to find a single remedy that encompasses the characteristic symptoms of this patient, as these symptoms represent the expressions of the illness. From the complaints listed above, the following symptoms are likely chosen because they are the most distinctive (PQRS: peculiar, queer, rare, and strange), intense, and/or causal for this patient and thus form the totality on which an appropriate remedy is sought:

- Fear of infections

- Early morning urge with diarrhea

- Foul-smelling stool

- Craving for spicy or seasoned food

- Dizziness that worsens in a warm room

As shown, some complaints are not included because they are not distinctive enough. There is only one remedy that matches the above totality of symptoms. According to the homeopathic materia medica, the remedy Sulphur best fits this combination of symptoms. To be clear, the prescription of Sulphur is not based on diagnoses or conditions such as dizziness, diarrhea, or anxieties. What is crucial is that one remedy is prescribed rather than separate treatments for digestive and skin complaints; these symptoms are addressed as expressions of the same underlying issue.

Similimum and a single remedy at a time

From the previous discussion, it is clear that Hahnemann (and most experienced and skilled homeopaths after him) believed in the existence of a single remedy that represents the similimum, and therefore, only one remedy should be prescribed at a time. Since prescribing one remedy at a time remains a somewhat controversial topic within contemporary homeopathy, we present several arguments here to demonstrate why this is a fundamental principle in our approach. Clarifying this similimum principle helps prevent confusion regarding what constitutes classical homeopathy and provides insight into the foundation upon which our practice is based. While other methods are, of course, possible, it can be confusing that such different approaches are often grouped together under the term ‘classical homeopathy.’

Organon

In the foundational text of classical homeopathy, the sixth edition of the Organon, Hahnemann clearly describes his approach of prescribing only one remedy at a time, selecting another only after assessing the effect of the initial remedy. For completeness, we present several relevant paragraphs with brief explanations.

In the foundational text of classical homeopathy, the sixth edition of the Organon, Hahnemann clearly describes his approach of prescribing only one remedy at a time, selecting another only after assessing the effect of the initial remedy. For completeness, we present several relevant paragraphs with brief explanations.

§110: “… for the pure, peculiar powers of medicines available for the cure of disease are to be learned neither … nor yet by the employment of several of them at one time in a mixture (prescription) in diseases …”

Note: Here, Hahnemann indicates that homeopathic remedies should never be given in combination or mixture.

§167: “… but we investigate afresh the morbid state in its now altered condition …”

Note: When a remedy is administered that partially matches the symptoms, another remedy is not simply prescribed. Instead, the new situation of the patient is first evaluated. This addresses the question of whether administering multiple remedies simultaneously or at intervals constitutes mixing. For Hahnemann, the time between two different remedies is irrelevant; precise evaluation of the altered state remains paramount.

§168: “… And thus we go on, if even this medicine be not quite sufficient to effect the restoration of health, examining again and again the morbid state that still remains, and selecting a homoeopathic medicine as suitable as possible for it, until our object, namely, putting the patient in the possession of perfect health, is accomplished.”

Note: This paragraph reiterates the principle from the previous section. Notably, the use of “a homeopathic medicine” in singular form emphasizes that the remedy should be a single, suitable one.

§192: “… to form a complete picture of the disease before searching among the medicines, … , for a remedy corresponding to the totality of the symptoms, so that the selection may be truly homoeopathic.”

Note: The “totality” referenced in this paragraph refers to all changes, complaints, and observable symptoms relevant to health. It does not pertain to a singular aspect but rather points to a single, fitting remedy.

§209: “… in order to be able to elucidate the most striking and peculiar (characteristic) symptoms, in accordance with which he selects the first antipsoric or other remedy having the greatest symptomatic resemblance, for the commencement of the treatment and so forth.”

Note: This section also refers to the remedy that best matches the overall characteristic symptoms of the patient.

This selection from the Organon underscores Hahnemann’s emphasis on prescribing a single, most-suited remedy that corresponds to the totality of the patient’s condition rather than a mixture of multiple treatments.

Krankenjournale

The Organon can be seen as a theoretical book on homeopathy, but it does not provide a complete picture of Hahnemann’s clinical practice. Fortunately, Hahnemann’s treatment records, known as the Krankenjournale, have been preserved. An analysis of the records from the last five years of his life, particularly Krankenjournal DF2 (ISBN 3830403550) and Krankenjournal DF5 (ISBN 3776012242), reveals that in 97% of consultations, Hahnemann prescribed only one remedy until the next consultation. In the rare cases where a second remedy was provided, he gave instructions for the second remedy to be taken once after a specified period. There is no indication of alternating remedies.

The Organon can be seen as a theoretical book on homeopathy, but it does not provide a complete picture of Hahnemann’s clinical practice. Fortunately, Hahnemann’s treatment records, known as the Krankenjournale, have been preserved. An analysis of the records from the last five years of his life, particularly Krankenjournal DF2 (ISBN 3830403550) and Krankenjournal DF5 (ISBN 3776012242), reveals that in 97% of consultations, Hahnemann prescribed only one remedy until the next consultation. In the rare cases where a second remedy was provided, he gave instructions for the second remedy to be taken once after a specified period. There is no indication of alternating remedies.

This approach in his later years likely reflects the method he deemed most effective and the way he ultimately wanted to shape homeopathic practice. It illustrates that Hahnemann’s practical approach almost always aligns with his theoretical descriptions in the Organon.

Although Hahnemann occasionally (in just 3% of consultations) prescribed a second remedy, it is clear that he nearly always provided only one remedy at a time to a patient. During a follow-up consultation, he carefully evaluated the remedy’s effect before considering a different one. This demonstrates that Hahnemann’s practical approach was almost entirely in line with the theoretical descriptions found in the Organon.

Remedy proving

Another important argument for prescribing only one remedy at a time stems from a fundamental concept in classical homeopathy: the remedy proving. In a proving, the specific effects of a single remedy on the health of an otherwise healthy person are studied. During such a proving, the subject receives a single remedy, after which any changes in health status are carefully observed. The entire materia medica is based on these provings. Each remedy is therefore tested without the influence of other remedies, to achieve a clear understanding of its specific effects.

It would be contradictory to administer multiple remedies simultaneously during treatment without evaluating their effects in between. Such an approach would not only create confusion about which remedy causes which effect but would also conflict with the foundation upon which the materia medica is built. In classical homeopathy, the aim is to find the one remedy that best fits the patient’s disease profile, with results carefully evaluated before potentially considering another remedy.

Hahnemann’s experiments with two remedies

It is sometimes argued that Samuel Hahnemann was a pioneer who did not explore everything. While this might be true for some things, it does not apply to the use of multiple remedies simultaneously. Hahnemann was a meticulous and thorough individual who took great care regarding his patients’ well-being. One of the ways this manifested was through his testing of different methods and approaches to optimize patient care. Methods that proved ineffective were rejected. One of his strengths was his openness to innovation rather than a rigid adherence to his system. This willingness to experiment led him to consider and test whether administering two remedies might benefit his patients more than a single remedy.

It is sometimes argued that Samuel Hahnemann was a pioneer who did not explore everything. While this might be true for some things, it does not apply to the use of multiple remedies simultaneously. Hahnemann was a meticulous and thorough individual who took great care regarding his patients’ well-being. One of the ways this manifested was through his testing of different methods and approaches to optimize patient care. Methods that proved ineffective were rejected. One of his strengths was his openness to innovation rather than a rigid adherence to his system. This willingness to experiment led him to consider and test whether administering two remedies might benefit his patients more than a single remedy.

In the biography Samuel Hahnemann: His Life and Work, written by Richard Haehl, we find an interesting passage in a letter dated June 17, 1833, to his close friend Boenninghausen. Hahnemann writes:

“… I too have made a beginning with smelling two suitable combined remedies and hope to have some good results …”

This indicates that he began testing two combined remedies to see if this approach could yield better results than using a single remedy. However, by September 15, 1833, he writes:

“… As it is never, as we know, absolutely necessary (although at times advantageous) to prescribe for the patient a double remedy, and the advantage gained from the exposition of this sometimes useful method, is, as I see, greatly overbalanced by the disadvantage which would certainly arise from a misinterpretation by the allopaths and allo-homoeopaths, I have, with your approval I feel sure, had the manuscript sent back to me, and have put everything back integrum, and also added a reprimand against such a proceeding, …”

Here, Hahnemann indicates that he concluded the use of two remedies simultaneously was unnecessary and that the drawbacks outweighed the benefits. He also feared that this method would be misunderstood by allopaths and other homeopaths, leading to confusion.

In later letters, he reiterates this position even more strongly. In his final letter on this subject, dated September 18, 1836, he writes:

“… that you have written to him and said that you now give two remedies together to your patients with much success? Has not even Aegidi, after much reflection, abandoned such an abominable heresy which gives the death blow to true homoeopathy, and throws it back to blind allopathy? … , and can therefore always be used suo jure as simple remedies, and give no excuse for that dangerous heresy and mixture.”

Here, Hahnemann goes so far as to state that combining remedies severely damages “true homeopathy” and that these remedies are more effective when used individually rather than combined.

From these quotations, it is clear that Hahnemann was open to testing multiple remedies simultaneously (without interim evaluation) to see if this would be more effective than single remedies. Ultimately, however, he concluded that this method was undesirable.

Methods that do not follow the similimum principle

There are other forms of homeopathy that do not adhere to the similimum principle as described in this article. These include:

- Clinical homeopathy: In this approach, remedies are prescribed based on a diagnosis, without consideration of the patient’s complete disease profile. This means that one or multiple remedies may be prescribed simultaneously, depending on the number of conditions, organs, or systems involved. For instance, Remedy A might be prescribed for sun allergy, while Remedy B is used for constipation.

- Complex homeopathy: This form involves prescribing combinations of remedies in the hope that one of the remedies will prove effective. An example is Urtizon complex, which consists of nine different low-potency remedies, aimed at alleviating certain skin conditions.

- Disease classification system: This method uses a predetermined schedule where different remedies are prescribed without interim evaluation of their effects. Each remedy in the schedule is tailored to one of eight specific conditions.

The similimum and our education program for classical homeopaths

In our educational program for classical homeopaths, the concept of the similimum is one of the key principles. Students learn how to select a remedy that best matches the complete symptom profile of each individual patient, and how to recognize and integrate all relevant symptoms and characteristics during the case-taking process.

Each homeopathic school of homeopathy has its own perspective on the similimum principle, and differences exist between them. This can lead to confusion not only for prospective students but also for individuals seeking help from a classical homeopath. For example, some programs emphasize prescribing one remedy at a time, while others may prescribe multiple remedies between consultations. As a result, two homeopaths might approach treatment quite differently, even though both identify as ‘classical homeopaths.’ Therefore, we encourage prospective students and those considering homeopathic treatment to carefully research their options. This helps prevent discovering during training or treatment that the chosen method does not align with one’s expectations, as switching schools is very difficult, expensive, and time-consuming.

Each homeopathic school of homeopathy has its own perspective on the similimum principle, and differences exist between them. This can lead to confusion not only for prospective students but also for individuals seeking help from a classical homeopath. For example, some programs emphasize prescribing one remedy at a time, while others may prescribe multiple remedies between consultations. As a result, two homeopaths might approach treatment quite differently, even though both identify as ‘classical homeopaths.’ Therefore, we encourage prospective students and those considering homeopathic treatment to carefully research their options. This helps prevent discovering during training or treatment that the chosen method does not align with one’s expectations, as switching schools is very difficult, expensive, and time-consuming.

In our program, we emphasize prescribing a single remedy that best matches the patient’s disease profile, followed by a careful evaluation of its effects after an appropriate period. This approach brings clarity, simplicity, and calm to the treatment process. Our foundation is not rooted in rigid adherence to Hahnemann’s teachings but in the practical, efficient, and clear structure that this method provides. Additionally, we observe that many influential homeopaths, such as Kent, Hering, Tyler, Allen, Boericke, Vithoulkas, Nash, and Lippe, have proven to be successful following this approach.

References used:

- Haehl, R. (2003). Samuel Hahnemann: His life and work (Vols. 1-2). B. Jain Publishers. (ISBN 8170216923; ISBN 817021694X)

- Hahnemann, S. (2002). Organon of Medicine (6th ed., translated by William Boericke). B. Jain Publishers. (ISBN 8170210852).

- Hahnemann, S. (2003). Krankenjournal DF2 (1st ed.). Sonntag Verlag. (ISBN 3830403550)

- Hahnemann, S. (1999). Krankenjournal DF5 (1st ed.). Haug Verlag. (ISBN 3776012242)