Introduction to the homeopathic classification of symptoms

In classical homeopathy, we use a classification based on where the symptoms manifest, in addition to characterizing them as characteristic (PQRS, intense, and causal) or non-characteristic. Thus, we have symptoms that appear locally or generally, physically or mentally. This classification helps in repertory search, differential diagnosis, and analyzing the response to treatment.

In classical homeopathy, we use a classification based on where the symptoms manifest, in addition to characterizing them as characteristic (PQRS, intense, and causal) or non-characteristic. Thus, we have symptoms that appear locally or generally, physically or mentally. This classification helps in repertory search, differential diagnosis, and analyzing the response to treatment.

How classical homeopathy categorizes symptoms

During homeopathic treatment, it is important to structure the patient’s narrative. You’ll receive a lot of information, and it’s essential to use it to find the most suitable remedy for the patient. To maintain clarity, it is helpful to categorize the patient’s symptoms.

In homeopathy, symptoms can be classified in two ways:

- Symptoms can be classified based on their characteristic or non-characteristic nature. This classification has already been explained in the article What is totality according to classical homeopathy?

- You can also classify symptoms based on the area affected. For instance, the mental or physical area. This article elaborates on symptom classification based on the area affected.

Note: There is also a method known as ‘disease classification’, developed by Ewald Stöteler. The classification in this method differs from what we use in this article.

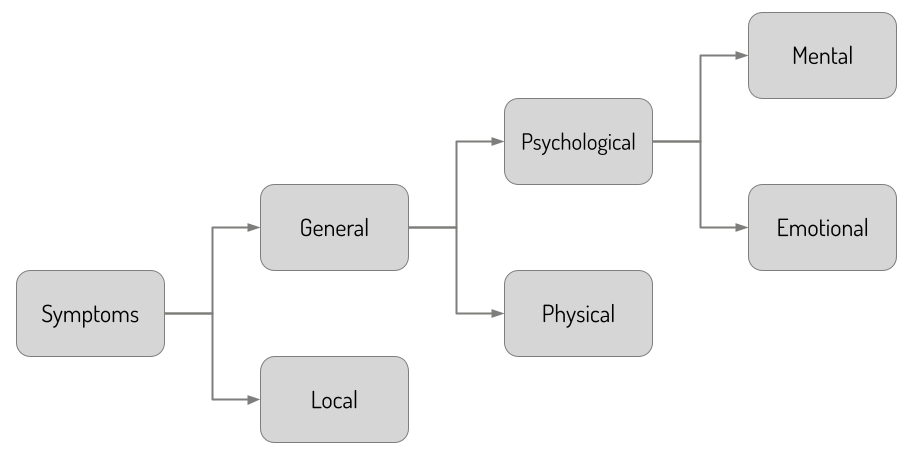

The classification of symptoms is illustrated in the diagram below and then explained further.

Local symptoms

According to classical homeopathy, local symptoms are those that pertain only to specific parts of the body, such as the head, knee, joints, a lung, digestion, skin, or glands. In these cases, the disease (see What is disease according to classical homeopathy?) manifests in a specific part of the body. Local symptoms are therefore always physical symptoms.

General symptoms

In contrast to local symptoms, which pertain to specific body parts, general symptoms in classical homeopathy affect the entire organism. This can be on a physical level, but also on a psychological level. For example, feeling too warm or cold often, feeling tired, being gloomy, not tolerating damp weather, having trouble reasoning, and having a fear of snakes.

Physical general symptoms

Physical general symptoms relate to the entire body. You could say they pertain to the tangible part of every human or living being. Physical general symptoms include fatigue due to sun exposure, always feeling cold, and poor reactions to certain types of food.

Psychological general symptoms

Psychological symptoms pertain to the intangible side of each individual patient. These include emotional and mental symptoms such as fears, concentration disorders, apathy, delusions, and so on.

It should be emphasized that some homeopaths also include things like character traits, hobbies, and other matters in this category that are not actually symptoms because they are not expressions of disease. If you look closely at the above schema, you will see that the first step is to only consider symptoms (= expressions of disease). You can read more about this in the article What are symptoms according to classical homeopathy?

Mental symptoms

Mental symptoms are those related to things like logic, reasoning, communication, memory, and so on. It pertains to the intellectual side of the psyche. Examples include forgetfulness, delusions, and concentration disorders.

Emotional symptoms

Emotional symptoms are those related to feelings, emotions, mood, and so on. Examples include fear of spiders, apathy, or problems with anger.

The purpose of symptom classification in classical homeopathy

This classification is useful for several reasons, as explained below.

Using the homeopathic repertory

You can use symptom classification to conveniently locate specific symptoms in the repertory. Mental generalities can be found in the chapter ‘MIND’ and physical generalities in the chapter ‘GENERALS’. By being aware of the area a symptom relates to, you can broadly determine where to search in the repertory.

You can use symptom classification to conveniently locate specific symptoms in the repertory. Mental generalities can be found in the chapter ‘MIND’ and physical generalities in the chapter ‘GENERALS’. By being aware of the area a symptom relates to, you can broadly determine where to search in the repertory.

Example: Suppose a patient has ‘germophobia’. Germophobia is a fear and thus falls under emotions. The diagram above shows that emotional complaints fall under mental complaints. In English, this translates to ‘MIND’. Therefore, the symptom ‘germophobia’ can be found in the repertory in the ‘MIND’ chapter.

Determining the value of a symptom

A general rule of thumb is that there is a hierarchy in the classification of symptoms when selecting useful ones. In principle, mental complaints are the most important, followed by emotional, physical general, and finally local physical complaints. In the above diagram, complaints are arranged from top to bottom.

That mental complaints are relatively more important than physical complaints generally relates to the fact that, overall, mental complaints have a greater impact on general well-being and daily functioning than physical complaints. We will provide more nuance and explanation in another article.

The idea that mental complaints are generally more important than emotional and physical complaints is nuanced in the article ‘What is the hierarchy of pathology according to classical homeopathy?’

This is a general rule of thumb, and the classification of characteristic and non-characteristic symptoms is, of course, more important.

Suppose a patient suffers from both severe germophobia and gout in the right big toe. In that case, germophobia is an emotional complaint, while gout is a local complaint (because the symptoms manifest in a relatively small part of the body). A local complaint ranks lower than an emotional complaint. If you only consider this, you would expect the remedy to primarily match the general complaints, such as germophobia in this example.

Suppose a patient suffers from both severe germophobia and gout in the right big toe. In that case, germophobia is an emotional complaint, while gout is a local complaint (because the symptoms manifest in a relatively small part of the body). A local complaint ranks lower than an emotional complaint. If you only consider this, you would expect the remedy to primarily match the general complaints, such as germophobia in this example.

It is important to note that this is only one aspect of determining the value of a symptom, and other aspects may also influence it.

Differentiating homeopathic remedies

Various homeopaths indicate that in cases of doubt between two remedies for a patient, you can use general symptoms to make the final choice. For example, James Tyler Kent writes in ‘Lectures on Homeopathic Philosophy’ (Chapter 30):

‘Without the generals of a case no man can practice Homoeopathy, for without these no man can individualize and see distinctions. After gathering all the particulars, one strong general rules out one remedy and rules in another.’

According to Kent, and confirmed by many other homeopaths, generalities are more important than local complaints in choosing between different remedies. The underlying idea is that general symptoms usually provide more information about the patient as an individual. Therefore, in selecting a remedy for the patient, it’s important to understand the difference between a general symptom and a local one.

Assessing the response to a homeopathic remedy

After giving the correct remedy, the patient often responds in various ways. General symptoms frequently change before local symptoms. This distinction is important when determining whether a response to a remedy is good or poor. In another article, we will delve deeper into analyzing the response to a remedy and adjusting the treatment accordingly.

Example: In the earlier-discussed case of a patient with germophobia and gout, with a properly chosen remedy, you would expect a change in the germophobia (first), possibly followed by changes in the gout. It may also be that both complaints improve simultaneously. However, it’s a less favorable sign if the gout changes first without affecting the germophobia.

The classification of symptoms during training as a classical homeopath

During training as a classical homeopath, you learn to practically apply the classification described in this article. It is not a goal in itself, but the classification can help you determine where to find certain symptoms in the repertory, which symptoms are important in assessing the response to the remedy, and so forth. The classification of symptoms serves not only an educational purpose but is essential for effective patient treatment in classical homeopathy.

During our training, students practice this classification intensively through lessons, paper cases, video cases, and internships. By the end of the first year, it has usually become second nature to most students. These exercises are expertly integrated into the other teaching materials.